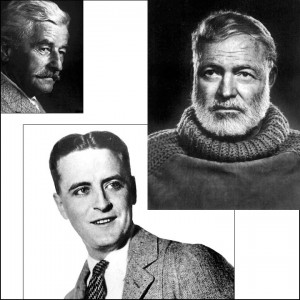

Four American writers born at the turn of the century defined modern America: John Steinbeck, F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, and Ernest Hemingway.

Steinbeck’s Place Among

Modern American Writers

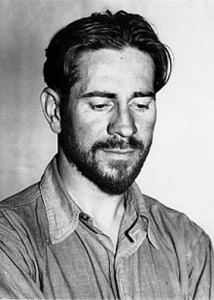

Among these American writers, only John Steinbeck lived long enough to experience the turbulent 1960s and frame important issues that trouble us today—political tyranny, economic inequality, and the willful destruction of our planet. Uniquely, books by author John Steinbeck depict the suffering of individuals with the goal of helping the masses understand other people and cope with their own lives. Steinbeck was the youngest of the four American writers and the most hopeful about the future, despite personal problems, political enemies, and attacks by critics. Books by author celebrities always attract opposition from academics, pundits, and politicians, but Steinbeck received more than his share.

In The Grapes of Wrath Steinbeck taught Americans how to feel empathy for the downtrodden, the despised, and the dispossessed. Like Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and other books by author-activists from an earlier era, Steinbeck’s proletarian novel—and its popular movie adaptation—mobilized public opinion as few books by other modern American writers succeeded in doing. Like Stowe’s 19th century antislavery story, Steinbeck’s 20th century epic of the Joads, Dust Bowl migrants in Depression-era California, has been translated everywhere and has never been out of print.

The Years Before The Grapes of Wrath

John Steinbeck was born on February 27, 1902, in Salinas, a small California community dominated by agricultural and business interests—the kind of self-satisfied American town satirized in Winesburg, Ohio, one of Steinbeck’s favorite books by author Sherwood Anderson.

The Mexican province of Alta California had been annexed by the United States a half-century earlier. In contrast to nearby Monterey—an historic and multicultural coastal town not far away—Salinas was an inland community populated primarily by whites. Many American writers of the period rebelled against the racism and rituals of hometowns like Salinas. John Steinbeck was no exception.

The Mexican province of Alta California had been annexed by the United States a half-century earlier. In contrast to nearby Monterey—an historic and multicultural coastal town not far away—Salinas was an inland community populated primarily by whites. Many American writers of the period rebelled against the racism and rituals of hometowns like Salinas. John Steinbeck was no exception.

As a child Steinbeck was a dreamer who didn’t quite fit the expectations of others, with a gift of invention for tall tales and written stories. As an adult he labored in solitude developing his craft, but didn’t publish his first novel until 1929, a month before the stock market crashed. He attended Stanford University off and on, taking the courses he liked, exploring San Francisco on weekends, and working at odd jobs to support his writing. In 1925 he hopped a freighter to New York, where he hauled cement at Madison Square Garden, worked unsuccessfully as a newspaper reporter, and failed to find a publisher for the short stories he ground out in a rented room.

Growing up amidst the fertile fields and gentle hills surrounding Salinas, Steinbeck enjoyed working with his hands and being outdoors. During summers and semesters away from Stanford, he dug ditches, tested sugar content, and labored alongside Mexicans, Filipinos, and others who provided rich material for his fiction.

Growing up amidst the fertile fields and gentle hills surrounding Salinas, Steinbeck enjoyed working with his hands and being outdoors. During summers and semesters away from Stanford, he dug ditches, tested sugar content, and labored alongside Mexicans, Filipinos, and others who provided rich material for his fiction.

While British and American writers like Fitzgerald and Hemingway were leading exciting lives as expatriates in 1920s Paris, Steinbeck pursued a contrary avenue of escape as a property caretaker in isolated Lake Tahoe. There he met Carol Henning, a kindred spirit from San Jose, California. A rebellious extrovert with a steady job in San Francisco, she was a good match for the struggling young writer, and they eventually got married. Her liberal politics further developed Steinbeck’s growing social consciousness.

Not long before their marriage the couple moved to Pacific Grove, California, where they attracted a circle of free-thinking friends and rising American writers from nearby Carmel and Monterey. For a period they lived in a funky part of Los Angeles, then in lush Los Gatos, a mountain town not far from San Jose. There Carol typed and edited John’s manuscripts and gave him the title for The Grapes of Wrath.

Big Books by Author-Activists

Big books by author-activists use up reservoirs of energy and emotion and the marriage didn’t last. Other American writers such as Hemingway had similar experiences. But Steinbeck was unusually shy and always feared fame, and the phenomenal success of The Grapes of Wrath in 1939 confirmed his worst anxieties about becoming a public person. Charlie Chaplin, Burgess Meredith, and a stream of stars came calling from Hollywood, where the movie version featuring Henry Fonda (who became John Steinbeck’s lifelong friend) was being filmed. Carol felt increasingly marginalized by the celebrity of her husband, one of the handful of American writers everyone was talking about. They were divorced in 1943 after living apart in California and New York.

The years preceding The Grapes of Wrath produced an outpouring of original books by author John Steinbeck. The Pastures of Heaven, To a God Unknown, In Dubious Battle, Tortilla Flat, The Long Valley, The Red Pony, and the experimental play-novelette Of Mice and Men, all are authentic works of genius that continue to inspire wonder, empathy, and understanding—what Steinbeck called participation—in readers of every age.

The years preceding The Grapes of Wrath produced an outpouring of original books by author John Steinbeck. The Pastures of Heaven, To a God Unknown, In Dubious Battle, Tortilla Flat, The Long Valley, The Red Pony, and the experimental play-novelette Of Mice and Men, all are authentic works of genius that continue to inspire wonder, empathy, and understanding—what Steinbeck called participation—in readers of every age.

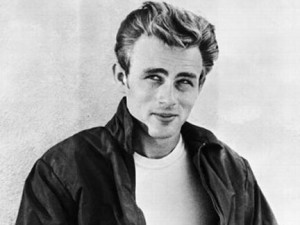

Of Mice and Men became a Broadway hit and a major movie starring Burgess Meredith. The Grapes of Wrath became an Academy Award-winning film, dramatically depicting the dignity of displaced farm families to millions of movie-lovers who (as today) hadn’t always read the book. Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz—two other Hollywood hits of the same period adapted from works by popular American writers—couldn’t be more different from three gritty Depression-era works by author John Steinbeck. In Dubious Battle, Of Mice and Men, and The Grapes of Wrath were reality, not escapism. Readers recognized their truthfulness, and they inspired generations of artists and musicians beginning with the folksinger Woody Guthrie. East of Eden achieved similar scope in 1952 and was also made into a popular film that, like The Grapes of Wrath, introduced an exciting young actor to American moviegoers and never lost its magic.

Between The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden

Rebelling against the Republican politics of his hometown of Salinas, Steinbeck became a New Deal Democrat and a strong supporter of FDR. When The Grapes of Wrath was denounced by conservatives, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt publicly defended the book’s accuracy. During World War II the author produced high-grade literary propaganda for the federal government and filed human-interest stories on U.S. military operations in North Africa and Italy.

Rebelling against the Republican politics of his hometown of Salinas, Steinbeck became a New Deal Democrat and a strong supporter of FDR. When The Grapes of Wrath was denounced by conservatives, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt publicly defended the book’s accuracy. During World War II the author produced high-grade literary propaganda for the federal government and filed human-interest stories on U.S. military operations in North Africa and Italy.

In 1945—married for the second time to a singer named Gwyn Conger and shuttling between California and New York—Steinbeck experimented with social satire in Cannery Row, set in post-war Monterey. Although the novel made Monterey famous and attracted tourists, it ruined Steinbeck’s relationship with former friends and, like The Grapes of Wrath, turned the establishment against him. Steinbeck’s novel The Wayward Bus, a cynical story also set in what is now known as Steinbeck Country, didn’t improve the author’s local popularity. Nor did his bitter public divorce from his second wife after the birth of two sons. (Both boys grew up in New York, served in Vietnam, and eventually became writers. Steinbeck said he wrote East of Eden to help them understand their California roots.)

Steinbeck maintained that he was always happiest in Monterey. There he met the future mythologist Joseph Campbell, a philosophical marine biologist named Edward Ricketts, and rising American writers who—like Ricketts and Campbell—deeply influenced Steinbeck’s developing thought. Eventually Steinbeck clashed with Campbell, as he did with others over his lifetime. But Ricketts—the alter ego who appears as a character in several Steinbeck novels—became the writer’s closest friend and collaborator. Together they wrote Sea of Cortez, a travel narrative and meditation on philosophical themes dramatized in Steinbeck’s fiction from the 1930s through East of Eden.

Steinbeck maintained that he was always happiest in Monterey. There he met the future mythologist Joseph Campbell, a philosophical marine biologist named Edward Ricketts, and rising American writers who—like Ricketts and Campbell—deeply influenced Steinbeck’s developing thought. Eventually Steinbeck clashed with Campbell, as he did with others over his lifetime. But Ricketts—the alter ego who appears as a character in several Steinbeck novels—became the writer’s closest friend and collaborator. Together they wrote Sea of Cortez, a travel narrative and meditation on philosophical themes dramatized in Steinbeck’s fiction from the 1930s through East of Eden.

Personal Depression and Recovery

Ricketts was killed in 1948, shortly before Steinbeck’s divorce from Gwyn, and the double punch drove the author into a state of despair. His third wife Elaine Anderson—a Texan who had become part of the Broadway theater scene—pulled him out of his depression. Married in 1950, the couple enjoyed an 18-year partnership as high-profile members of the Manhattan celebrity set made up of American writers, actors, and musicians just as famous as John Steinbeck. Although New York became the couple’s home and they traveled throughout the world, Steinbeck’s novel East of Eden shows that he never forgot California.

Published in 1952, East of Eden was made in 1955 into the film classic starring James Dean. Steinbeck’s saga tells the story of two Salinas Valley families—the Hamiltons and the Trasks—over three generations. Other American writers of Steinbeck’s time, including Faulkner, produced similar storylines from autobiographical material. But few wrote with Steinbeck’s deep sense of personal participation or passion for the past, and only East of Eden was adapted for television as well as the movies.

Published in 1952, East of Eden was made in 1955 into the film classic starring James Dean. Steinbeck’s saga tells the story of two Salinas Valley families—the Hamiltons and the Trasks—over three generations. Other American writers of Steinbeck’s time, including Faulkner, produced similar storylines from autobiographical material. But few wrote with Steinbeck’s deep sense of personal participation or passion for the past, and only East of Eden was adapted for television as well as the movies.

That may be why critics complained so bitterly about his next novel, Sweet Thursday. A slight comedy with a brittle center, it brings the characters of Cannery Row up to date—sadder, older, but no wiser—and completes the Monterey trilogy begun by Steinbeck with Tortilla Flat. Like The Wayward Bus, Steinbeck’s 1947 novel about sexual hypocrisy and self-delusion, Sweet Thursday lacks the sense of redeeming social value required by moralists with literal minds. Most readers loved the book anyway (Steinbeck always said he wrote for the public, not the critics), and Broadway became interested.

But Sweet Thursday proved to be too risqué for Oscar Hammerstein II, who collaborated with Richard Rodgers and Steinbeck to produce Pipe Dream, the musical comedy version. Hammerstein didn’t believe audiences were ready for scenes set in a whorehouse, despite the author’s warning that times had changed by 1955. Hammerstein’s sentimental treatment of Steinbeck’s tough little story diluted Steinbeck’s hardboiled characters, and the show failed. Burning Bright, Steinbeck’s avant-garde play, proved even more confusing to Manhattan theater critics.

But Sweet Thursday proved to be too risqué for Oscar Hammerstein II, who collaborated with Richard Rodgers and Steinbeck to produce Pipe Dream, the musical comedy version. Hammerstein didn’t believe audiences were ready for scenes set in a whorehouse, despite the author’s warning that times had changed by 1955. Hammerstein’s sentimental treatment of Steinbeck’s tough little story diluted Steinbeck’s hardboiled characters, and the show failed. Burning Bright, Steinbeck’s avant-garde play, proved even more confusing to Manhattan theater critics.

Politics and Critics Burning Bright

Working with New Yorkers had been challenging for Steinbeck before. His literary agent insisted on softening the profanity in the dialog of The Grapes of Wrath, and his publisher initially rejected In Dubious Battle for failing to portray Communism (never mentioned in the book) more accurately. Unlike Faulkner, Fitzgerald, and other American writers, however, Steinbeck generally worked well with Hollywood. Books by author-screenwriters—even those as talented as Steinbeck—don’t always translate to film without problems. When Alfred Hitchcock introduced racial stereotyping into Steinbeck’s story for the wartime film Lifeboat, the writer was so angry that he tried to have his name removed from the credits. Hitchcock, the British director of Vertigo and other thrillers shot in California, was a middle-class snob, a species Steinbeck learned to despise during his childhood in Salinas and his years in Monterey.

Steinbeck reacted to Stalinist communism the same way he did to social snobbery—with vigor. His opposition to the Soviet system and his affection for the Russian people are both evident in A Russian Journal, the result of his collaboration with the photographer Robert Capa following their tour of the USSR in 1947. It was one of three trips the author made to Russia, where his work remains popular.

Steinbeck reacted to Stalinist communism the same way he did to social snobbery—with vigor. His opposition to the Soviet system and his affection for the Russian people are both evident in A Russian Journal, the result of his collaboration with the photographer Robert Capa following their tour of the USSR in 1947. It was one of three trips the author made to Russia, where his work remains popular.

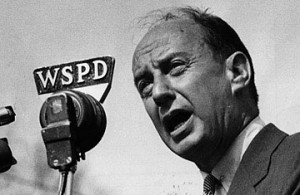

While attacking dictatorship behind the Iron Curtain, Steinbeck was also denouncing McCarthyism, Madison Avenue, and mindless consumerism back home in America. He disliked Eisenhower, distrusted Nixon, and actively supported Adlai Stevenson for president in 1952 and 1956. Stevenson’s individualism, idealism, and progressivism are prefigured in Steinbeck’s major fiction of the 1930s, and they continued in his novels, plays, and nonfiction up to the 1960s. The Forgotten Village, The Pearl, and Zapata—enduring examples of Steinbeck’s Stevensonian populism—are all set in Mexico, a land the writer loved almost as much as Monterey. But by the late 1950s, political reality was obtruding on the author’s hope for human brotherhood. The Short Reign of Pippin IV—Steinbeck’s caricature of current French politics—shows what happens when an idealist like Stevenson gets into office and tries to change the system.

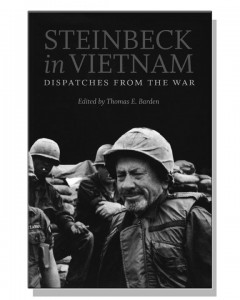

Elaine and John Steinbeck were invited to President Kennedy’s inauguration and became welcome guests in the Johnson White House, where Elaine and Lady Bird could reminisce about schooldays together at the University of Texas. Just as First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt had stood up for Steinbeck when he was under attack for writing The Grapes of Wrath, Steinbeck defended President Johnson from critics of American policy in Vietnam. In private Steinbeck expressed doubts about the war, but his public loyalty damaged his reputation among authors, academics, and some friends. Steinbeck made it a point to avoid criticizing other writers. Not all of them returned the favor. Steinbeck was sensitive, and the attacks hurt.

Elaine and John Steinbeck were invited to President Kennedy’s inauguration and became welcome guests in the Johnson White House, where Elaine and Lady Bird could reminisce about schooldays together at the University of Texas. Just as First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt had stood up for Steinbeck when he was under attack for writing The Grapes of Wrath, Steinbeck defended President Johnson from critics of American policy in Vietnam. In private Steinbeck expressed doubts about the war, but his public loyalty damaged his reputation among authors, academics, and some friends. Steinbeck made it a point to avoid criticizing other writers. Not all of them returned the favor. Steinbeck was sensitive, and the attacks hurt.

The author of The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden was already old-fashioned to America’s literary establishment when (following Lewis, Faulkner, Hemingway, and the American writer Pearl Buck) he won a Nobel in Literature in 1962. Despite delivering an acceptance speech exalting individualism and damning the Cold War, Steinbeck’s war dispatches from Vietnam four years later gave his enemies ammunition, and the assault on his reputation continued even after he died. How ironic for a writer who exposed the insanity of war fever in books from Cup of Gold (his first novel) to The Moon Is Down (his World War II play-novelette). How unfair to the author of East of Eden, depicting three bloody conflicts—the Civil War, the Indian wars, and World War I—feeding private corruption and public hysteria on a monumental scale. How painful for a father with two sons in the service.

Steinbeck’s Enduring Message of Warning and Hope

The 1960s were stressful for Steinbeck, and his personal decline reflects the turmoil that sensitive people suffer for unresolved inner conflicts as they age. Before his death in 1968, the author published three books that convey his deep ambivalence about developments in America. Travels with Charley, The Winter of Our Discontent, America and Americans—uneven experiments in fiction, fact, and form—all portray a post-moral culture using post-modernist literary techniques.

The 1960s were stressful for Steinbeck, and his personal decline reflects the turmoil that sensitive people suffer for unresolved inner conflicts as they age. Before his death in 1968, the author published three books that convey his deep ambivalence about developments in America. Travels with Charley, The Winter of Our Discontent, America and Americans—uneven experiments in fiction, fact, and form—all portray a post-moral culture using post-modernist literary techniques.

Each book sold well despite Steinbeck’s darkening outlook. The Winter of Our Discontent ends ambiguously, leaving readers to wonder what will become of its flawed hero, Ethan Hawley. Like The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden, the ending of Steinbeck’s last novel allows readers to participate by imagining for themselves how things will turn out. Survival and destruction are equally possible outcomes in Steinbeck’s most memorable novels. He loved music with a passion, but his best pieces end without a final chord.

Taken together, Steinbeck’s three final books diagnose symptoms of social decay—racism and homophobia, consumerism and corruption, environmental destruction and deadening self-involvement—that continue today. Unlike Faulkner, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and other modern American writers, John Steinbeck remains fresh and relevant to contemporary readers of almost every age and type, raising questions of power and poverty, individualism and community, in warning and in hope.